"Boys On Tour"

The Ypres Salient

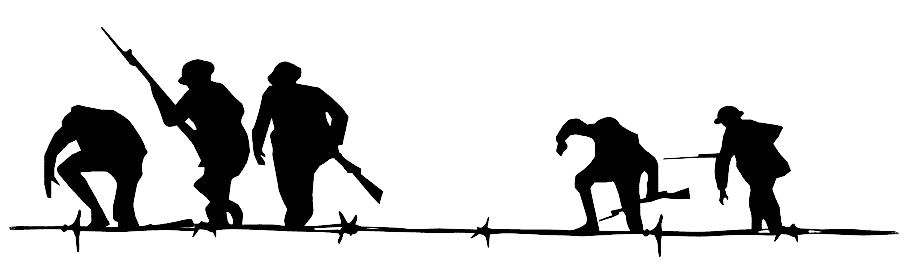

The Ypres Salient was a dangerous, bulge-shaped area in the Western Front lines during World War I, where Allied forces (primarily British, French, Canadian, and Belgian) were surrounded on three sides by German forces. This salient, formed during the “Race to the Sea” in 1914, made the troops within vulnerable to attacks from multiple directions.

Here’s a simpler breakdown:

What it was:

A section of the front line that bulged inwards towards the German side, creating a salient.

Why it was important:

The Allies were trying to protect the key port towns of Calais and Boulogne, which were vital for supplies.

How it was formed:

The Allies fought the German advance to a standstill, but in doing so, they created a bulge in their own lines that was surrounded on three sides by the enemy.

Why it was dangerous:

Soldiers in the salient were constantly under fire from multiple directions, making it a very dangerous place to be.

Key battles:

Several major battles were fought in and around the Ypres Salient, including the First, Second, and Third Battles of Ypres (also known as Passchendaele).

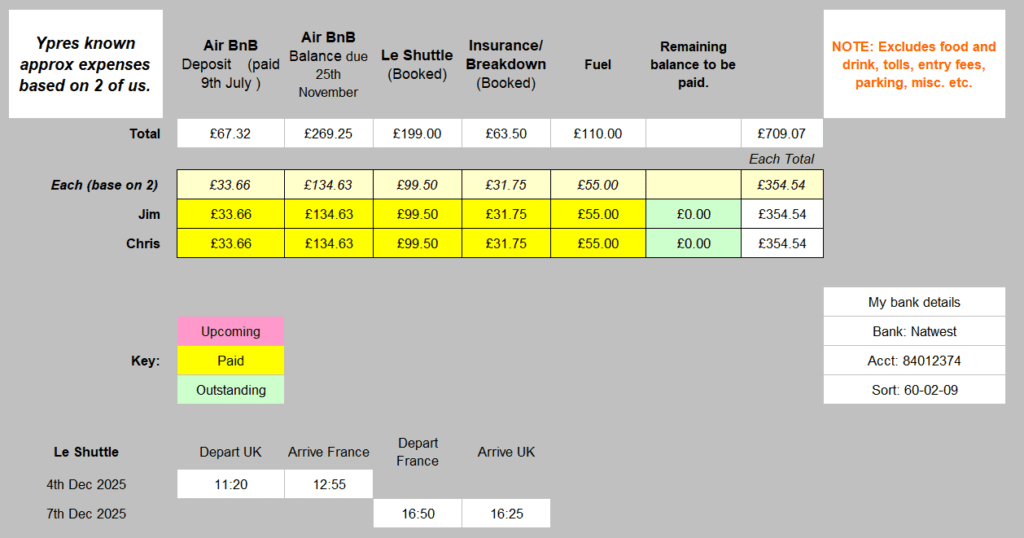

Troop deployment December 2025…..

Mission: Belgium 2025

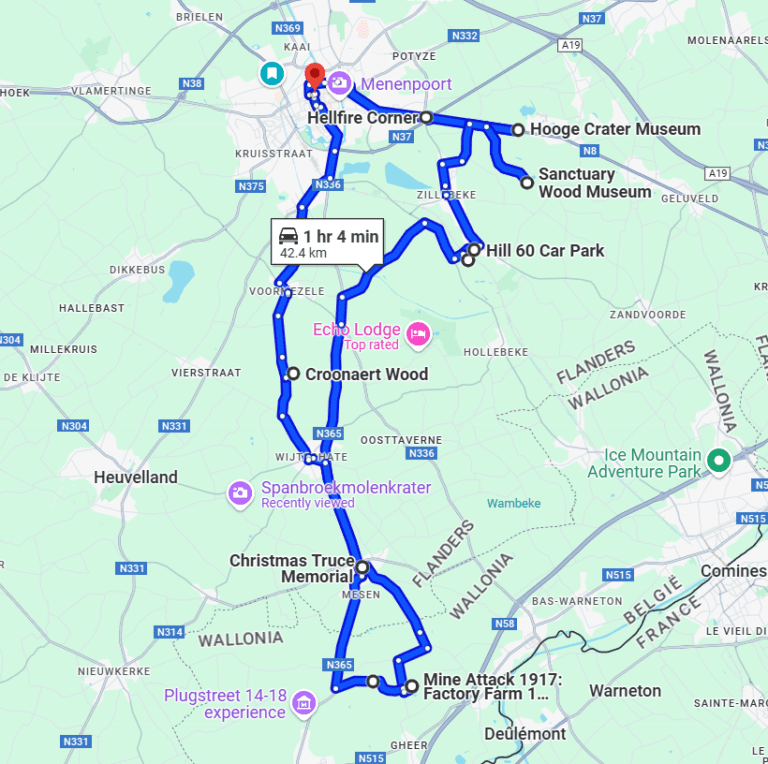

Hell Fire Corner

Hellfire Corner was a junction in the Ypres Salient in the First World War. The main supplies for the British Army in this sector passed along the road from Ypres to Menin – the famous Menin Road. A section of the road was where the Sint-Jan-Zillebeke road and the Ypres-Roulers railway crossed the road.

Hooge Crater

Sanctuary Wood and British trenches.

After the First World War a farmer returned to reclaim his land in and around what was left of the wood he had left in 1914. A section of the original wood and the trenches in it were cleared of debris and casualties but generally the farmer left a section of a British trench system as he found it.

This site is now one of the few places on the Ypres Salient battlefields where an original trench layout can be seen in some semblance of what it might have looked like. Elsewhere the trenches were filled in and ploughed over by returning farmers leaving only the occasional chalky outline of what had once been there.

In the last decade there has been a large increase in visitors to the Ypres Salient, and many have, of course, included a visit to the trenches at Sanctuary Wood. In the 1990s the trenches were covered in grass and the whole site was overgrown with undergrowth. Interestingly, nowadays the ground around the trench line has been visited by so many pairs of feet that it is mostly bald with no grass or undergrowth. The photograph on the far right shows how the trenches looked just a few years ago.

The need for the preservation of battlefield areas makes for an interesting discussion. The natural desire to be allowed to walk freely amongst historical remains such as these trenches is one side of the argument, the possibility that they will be damaged in so doing is another. It’s been a topic of discussion for some years already by battlefield historians, local authorities and the people who live with the scarred landscape all around them. Sanctuary Wood is a fascinating example of how such war remains bring together the local people who own the ground and live with them daily, the people who come in their thousands each year to see them, historians who debate whether these trench remains are original or not, and the people who want to find ways to preserve endangered WW1 battlefield remains.

The Sanctuary Wood trench museum is privately owned by the grandson of the farmer who reclaimed his land in 1919 when the local people returned to Ypres.

Hill 62 battlefield overview.

The Battle of Mont Sorrel (Battle of Mount Sorrel, Battle of Hill 62) was a local operation in World War I by three divisions of the British Second Army and three divisions of the German 4th Army in the Ypres Salient, near Ypres in Belgium, from 2 to 13 June 1916.

To divert British resources from the build-up being observed on the Somme, the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps and the 117th Infantry Division attacked an arc of high ground defended by the Canadian Corps. The German forces captured the heights at Mount Sorrel and Tor Top, before entrenching on the far slope of the ridge. Following a number of attacks and counterattacks, two divisions of the Canadian Corps, supported by the 20th Light Division and Second Army siege and howitzer battery groups, recaptured the majority of their former positions.

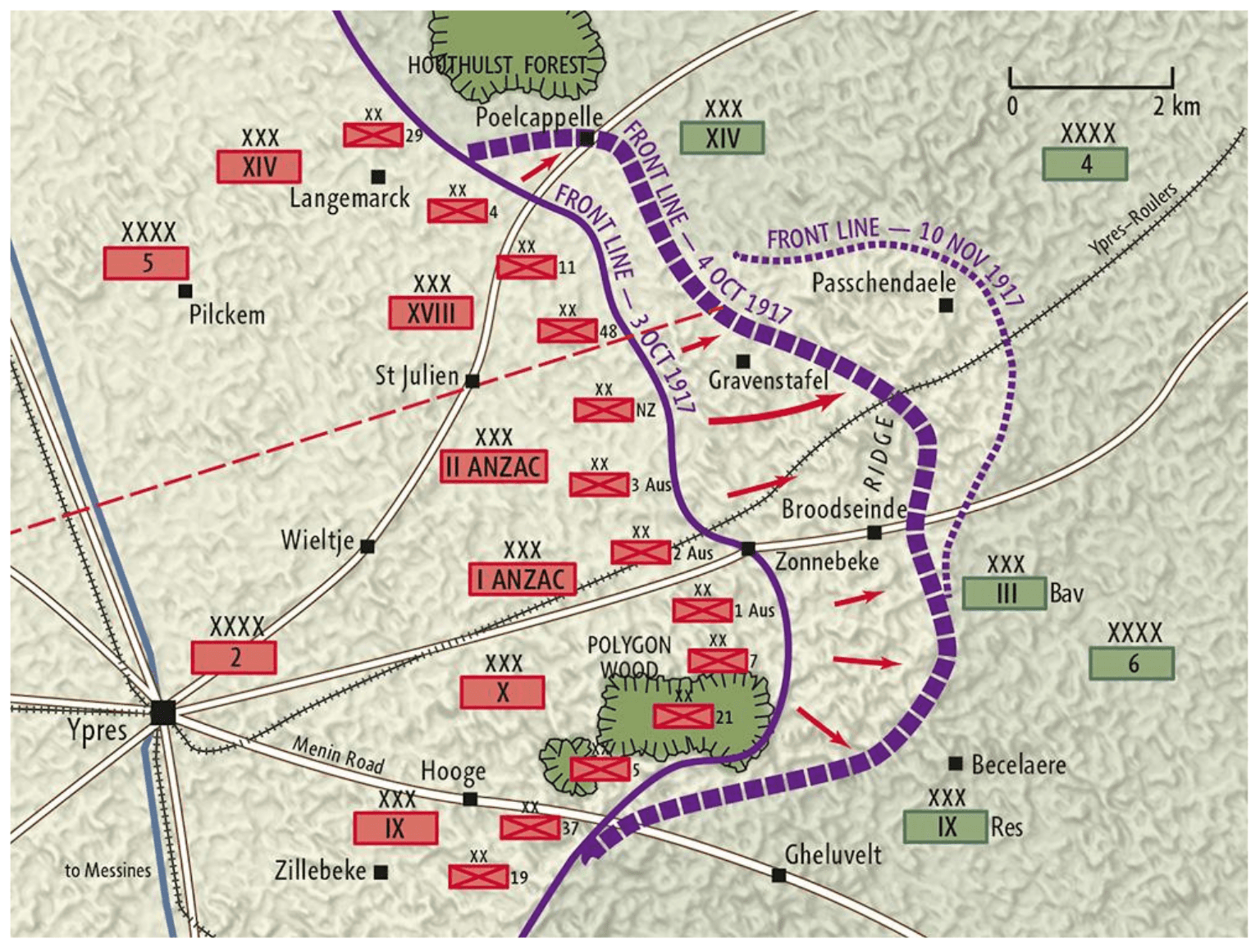

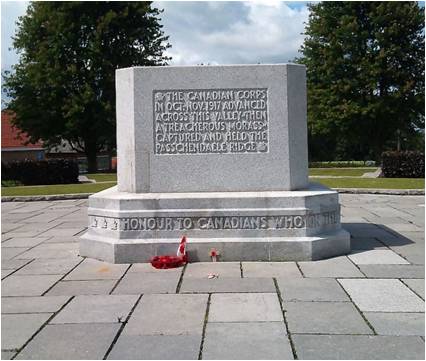

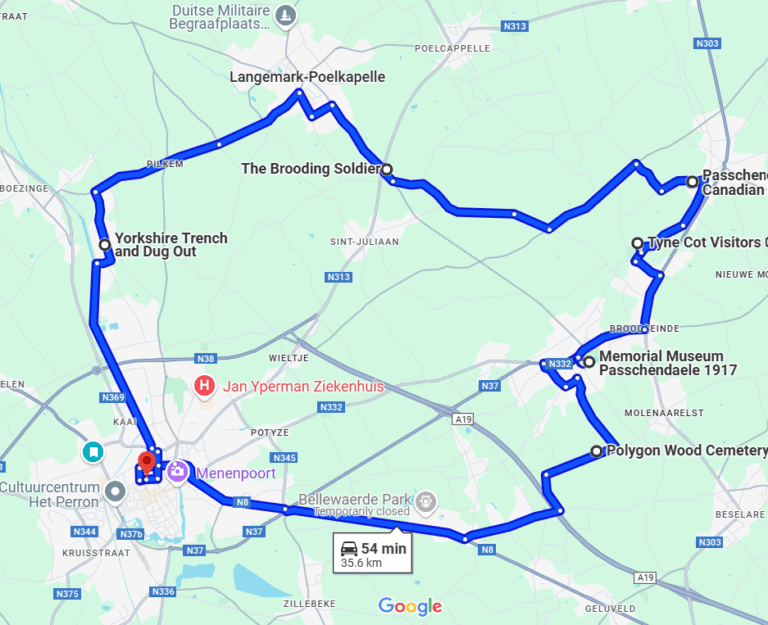

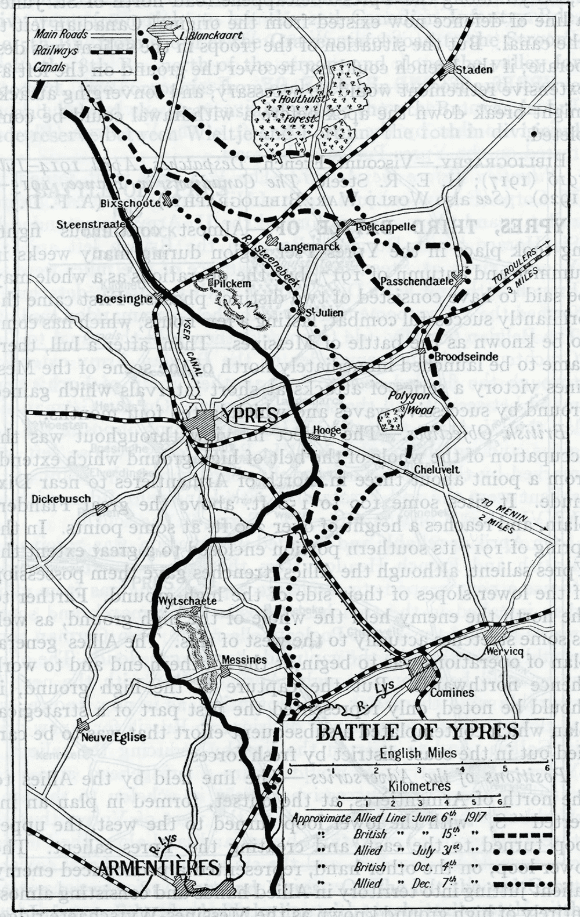

The final phase, the advance on Passchendaele, took place in October and November, the aim being to take the strategically important high ground of the Passchendaele ridge. The first battle of Passchendaele, on the 12th October, failed to take the village, and the second battle of Passchendaele lasted from the 26th of October until the 10th of November. The map below shows the sites described on this page. Just south west of the village is the large cemetery and Memorial to the Missing at Tyne Cot.

Hill 60 preserved battlefield and bunkers.

Hill 60 is a World War I battlefield memorial site and park in the Zwarteleen area of Zillebeke south of Ypres, Belgium. It is located about 4.6 kilometres (2.9 mi) from the centre of Ypres and directly on the railway line to Comines. Before the First World War the hill was known locally as Côte des Amants (Lover’s Knoll). The site comprises two areas of raised land separated by the railway line; the northern area was known by soldiers as Hill 60 while the southern part was known as The Caterpillar.

Caterpillar Crater.

See above

The Caterpillar mine crater is inextricably linked to the history of mine warfare on Hill 60. Both originated from the same tunnel system. Hill 60 is the English name for a sector on the front of the First World War, where the Ypres-Kortrijk railway ‘cuts through’ the central West Flemish ridge. During its construction shortly before 1854, the track was laid in a bed here, so that the train did not have to cross the ridge, but ran through it. The excavated earth was deposited on both sides of the railway line. This created three artificial elevations, namely Hill 60 north of the railway, the Caterpillar on the south side and the Dump. The site takes its name from the height above the water level (60m). The elongated, undulating mound of earth south of the railway reminded British war cartographers of a caterpillar . Because the location developed into a tourist site after the war, the British wartime toponyms had the opportunity to take root in the current place names. Due to its higher location, Hill 60 had a good view of the south-east of Ypres. The site was 4.3 km as the crow flies from the main market. Hill 60 was right on the front from 1914 to mid-1917. In June 1917, the northernmost deep mine exploded here.

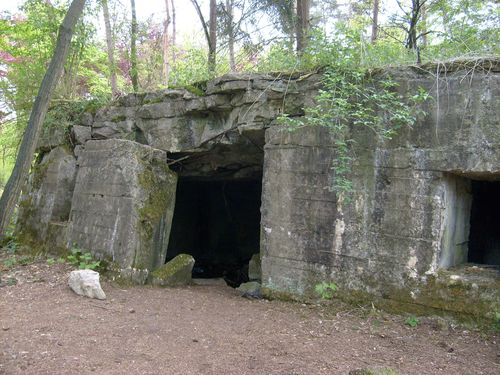

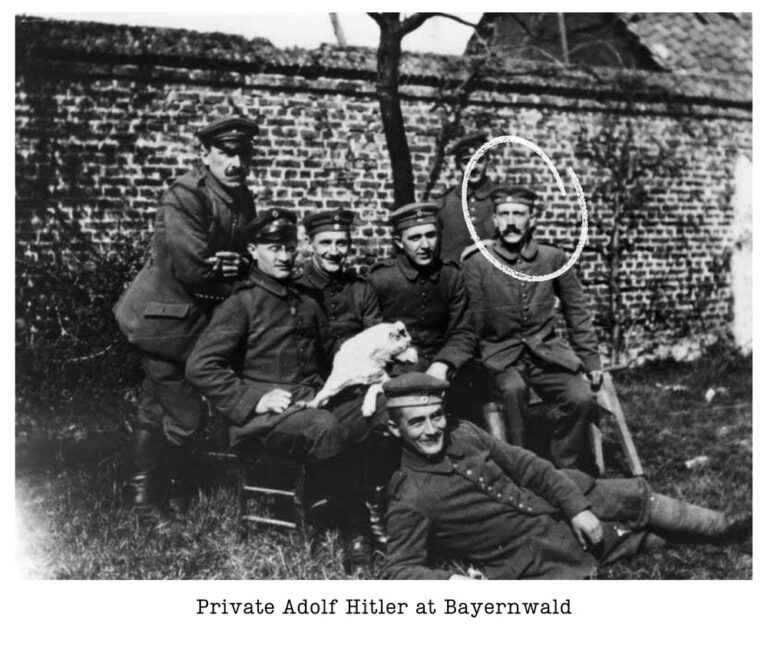

Byernwald German Trenches

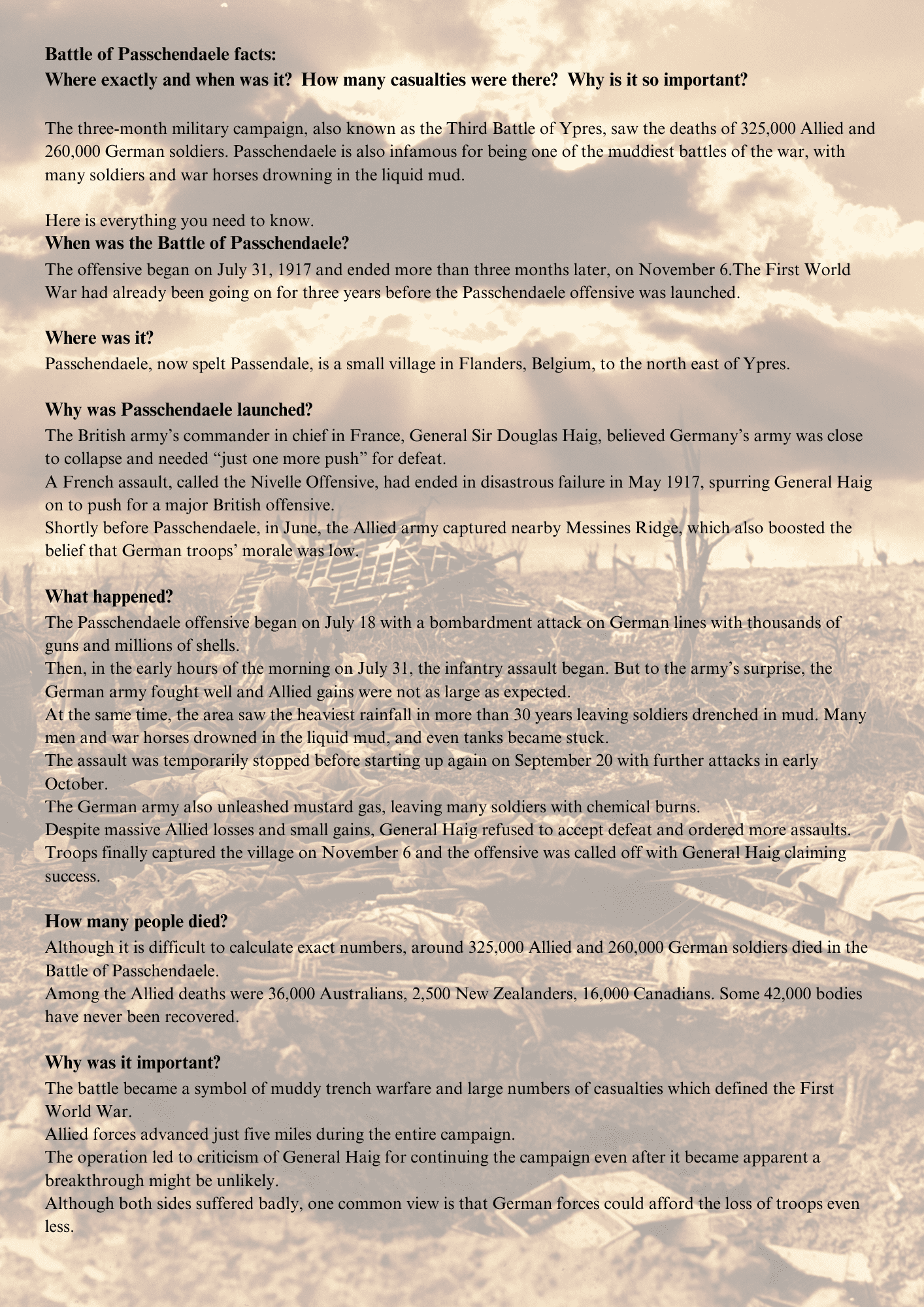

The Bayernwald Trenches are a carefully restored section of an original German trench system dating from 1916. The reconstruction was carried out in the original trench section under archaeological conditions.

The trench system allows visitors to walk through a significant area of German trenches, which include the following features:

- sandbagging

- trench sides made of woven wickerwork branches

- duckboard walkways

- stone and reinforced concrete dugouts

- mine shaft “Berta 4” (secured and covered)

Christmas Truce Monument of 1914.

The devil is often said to be in the detail, but not in this story. On 24 December 1914, something extraordinary happened amid the hellish killing fields of the Western Front. German and Allied troops, mercilessly slaughtering each other just hours earlier, laid down their arms and embraced Christmas together. In one of the most poignant events in human history, sworn enemies dropped their weapons, clambered out of trenches and crossed the shell-blasted mud of no-man’s land to shake hands, sing carols and exchange gifts. The British brought Bully beef, rum and cigarettes to the party. In exchange, the Germans traded sausages, coffee and cognac. Then, famously, a football match was played. To be precise, a small number of football matches were played, up and down the length of the 500-mile front line. Out of necessity, many deployed a rolled up sandbag or tin can as an emergency football. But here and there a genuine leather ball was produced and a more serious match attempted. The largest shell craters were hastily filled in, referees were picked and military helmets or caps were placed as goalposts. The most famous of these impromptu international football matches occurred at St Yvon in southern Belgium, around eight miles south of Ypres. Here, in the fields of the Walloon village of Ploegsteert – known to the Tommies as “Plugstreet” – Saxon troops played their British counterparts on the slender strip of soil dividing the two armies. The Germans had started it. The unofficial truce began on 24 December – the day they traditionally celebrated Christmas – when they began decorating the frosted parapets of their trenches with candles and Christmas trees. Carols followed, including a rendition of ‘Stille Nacht.’ The British responded from across no-man’s-land with ‘The First Noel.’ And so it continued until, when the British sang ‘O Come All Ye Faithful,’ they heard the Germans joining in with the Latin words. Finally, a German messenger raised a white flag and strode boldly across the lines to broker the Christmas ceasefire.

Battlefields of Passchendaele

Now spelt Passendale, the small village of Passchendaele five miles north-east of Ypres is the name by which the final stages of the Third Battle of Ypres is known. It is the name, along with the Somme, which has come to symbolise the Great War for many. The Third battle of Ypres was preceded by the attack on Messines ridge in June 1917. The main battle commenced on the 31st of July 1917, and stretched on until November the 10th, 1917.

Tyne Cot Cemetery,

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) burial ground for the dead of the First World War in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. It is the largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, for any war. The cemetery and its surrounding memorial are located outside Passendale, near Zonnebeke in Belgium.

![]()

![]()

Brooding Soldier memorial.

The St. Julien Memorial, also known as The Brooding Soldier, is a Canadian war memorial and small commemorative park located in the village of Saint-Julien, Langemark (West Flemish: Sint-Juliaan), Belgium. The memorial commemorates the Canadian First Division‘s participation in the Second Battle of Ypres of World War I which included fighting in the face of the first poison gas attacks along the Western Front. The memorial was designed by World War I veteran and architect, Lieutenant Frederick Chapman Clemesha, and was selected following a design competition organized by the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission in 1920.

St. Georges Memorial Chapel

Saint George’s Memorial Church, Ypres (Ieper), Belgium, was built to commemorate over 500,000 British and Commonwealth troops, who had died in the three battles fought for the Ypres Salient, during World War I. It was completed in 1929.

Essex Farm dressing station bunkers.

The cemetery was established next to a dressing station established by the Canadian Field Artillery during the Second Battle of Ypres, on farmland which was unnamed on pre-war maps; the dressing station was operational from early 1915 until 1918. The name “Essex Farm” commemorates the Essex Regiment, perhaps because a soldier of the 2nd Battalion of the Essex Regiment was an early interment there in June 1915. Twenty eight members of the 11th Battalion of the Essex Regiment were also buried there during 1916.[2] A monument in the cemetery commemorates the composition of the war poem In Flanders Fields which is reported to have been written in May 1915 by Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae MD, after witnessing the burial of his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, of the 2nd Battery, 1st Brigade Canadian Field Artillery, at Essex Farm; Helmer’s grave is now lost.

Langemark German Cemetery.

The German war cemetery of Langemark (formerly spelt ‘Langemarck’) is near the village of Langemark, part of the municipality of Langemark-Poelkapelle, in the Belgian province of West Flanders.[1] More than 44,000 soldiers are buried here.[2] The village was the scene of the first gas attacks by the German army in the western front (see trench map), marking the beginning of the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915.

During the First Battle of Ypres (1914) in World War I, inexperienced German infantry suffered severe casualties when they made a futile frontal attack on allied positions near Langemark and were checked by experienced French infantry and British riflemen. Contrary to popular myth, only fifteen percent of the German soldiers involved in the Battle of Langemark were schoolboys and students. Legend has it that the German infantry sang the first stanza of what later (1919) became their national anthem “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles“, as they charged.

The cemetery, which evolved from a small group of graves from 1915, has seen numerous changes and extensions. It was dedicated in 1932. Today, visitors find a mass grave near the entrance. This comrades’ grave contains 24,917 servicemen, including the Ace Werner Voss.[3] Between the oak trees, next to this mass grave, are another 10,143 soldiers (including 2 British soldiers killed in 1918). The 3,000 school students who were killed during the First Battle of Ypres are buried in a third part of the cemetery. At the front of the cemetery is a sculpture of four mourning figures by Professor Emil Krieger. The group was added in 1956, and is said to stand guard over the fallen. The cemetery is maintained by the German War Graves Commission, the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge.

Otherwise, this cemetery has two Commonwealth burials.

Ploegsteert Memorial to the missing

The Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) memorial in Belgium for missing soldiers of World War I. It commemorates men from the Allied Powers who fought on the northern Western Front outside the Ypres Salient and whose graves are unknown. The memorial is located in the village of Ploegsteert and stands in the middle of Berks Cemetery Extension.

Ypres Information

Ypres

Today it is a small, pretty city in the far north-west of Belgium, noted for its imposing cloth hall built in the Middle Ages.

But one hundred years ago the nondescript Flemish town of Ypres was home to some of the most brutal and horrifying battles of World War One.

Five major battles were fought near the Dutch-speaking city between 1914 and 1918, causing hundreds of thousands of casualties on both sides.

Ypres itself became a byword for the destruction caused by WWI, with pictures from the conflict showing how the city was left in ruins at the end of the war.

There were more than 100,000 casualties in the First Battle of Ypres, from October 19 to November 22, 1914, with a similar number of casualties in the Second Battle of Ypres from April 22 – May 15 1915.

The Battle of Passchendaele, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, was fought around five miles from the city from July to November 1917.

The three-month military campaign, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, saw the deaths of 325,000 Allied and 260,000 German soldiers.

Passchendaele is also infamous for being one of the muddiest battles of the war, with many soldiers and war horses drowning in the liquid mud.

In 1918 the Battle of Lys, fought from April 7-29 as part of the Spring Offensive, resulted in around 200,000 casualties while there were around 10,000 casualties following the Fifth Battle of Ypres from September 28-October 2 1918.

Ypres bore the brunt of these brutal battles as it occupied a strategic position during the war, standing in the way of Germany’s planned march through Belgium as part of the Schlieffen Plan.

The Germans bombarded the city for most of the war and photos from the time document how it was completely flattened.

But the city bounced back and was rebuilt using money that Germany had paid in reparations, and now enjoys the title of \”city of peace\”, which it shares with Hiroshima, another city which witnessed warfare at its most brutal and destructive.

German command bunker at Zandvoorde.

A First World War German reinforced concrete Command Post bunker has been preserved as part of a restoration project by the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917. The command post has been a listed monument since April 1999.

The bunker was built with reinforced concrete in 1916 by the 3rd Company of Armierungsbatallion Number 27. The men of the Company inscribed a concrete plaque with these details, and this still survives on the bunker today. An Armierungsbatallion was a labour unit in the Imperial German Army.

The bunker was used as a command post for a German regiment in reserve in this sector. In 1916 the Front Lines were approximately 5-6 kilometres to the north-west of this position.

The bunker is 19 metres long. The roof has protective layer of earth about 1-1.70 metres deep.

There are six rooms in the bunker leading off a hallway. The rooms include:

- two rooms: one for the sentries watch post and one for their accommodation

- two rooms: two Staff officers’ work rooms

- two rooms: two Staff officers’ accommodation rooms

The Great War - Timeline

1914

- 28 June–Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated

- 28 June–Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia

- 29 July–Austria invaded Serbia

- 1 August–Germany declared war on Russia

- 2 August–Germany invaded Luxembourg

- 3 August–Germany declared war on France

- 4 August–Germany invaded Belgium

- 4 August–Great Britain declared war on Germany

- 6 August–Austria declaration of war on Russia

- 12 August–French and British declaration of war on Austria-Hungary

- 23 August–Battle of Mons (British Expeditionary Force)

- 1 October–The first division of Canadian troops sailed to complete its training in Great Britain

- 21 October-17 November–Germany failed to reach the English Channel in the First Battle of Ypres

- 2 November–Russia and Serbia declared war on Turkey

- 5 November–Britain and France declared war on Turkey

1915

- 11 February–The first Canadian soldiers land in France

- 22 April-25 May–The Second Battle of Ypres

- 25 April–Landing of British and French troops at Gallipoli

- 26 April–Secret Treaty of London between England, France, Russia, and Italy

- May-June–The Actions at Festubert and Givenchy

- 23 May–Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary

- 19 December–Beginning of the Allied withdrawal from Gallipoli

1916

- 21 February–Beginning of the Battle of Verdun

- 31 May-1 June–Battle of Jutland

- 2 June-13 June–The Battle of Mount Sorrel

- 4 June–Russia began offensive in eastern Galicia

- 1 July-18 November–Battle of the Somme

- 27 August–Italy declared war on Germany

1917

- 1 February–Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare

- 6 April–The United States declared war on Germany

- 9 April-4 May–Battle of Arras

- April-May–Battle of the Scarpe

- 26 June–American troops began landing in France

- 31 July-9 August–Germany ended Russia’s last offensive

- 31 July-10 November–Third Battle of Ypres

- 20 August-15 December–Second Battle of Verdun

- 27 November–Supreme Allied War Council established at Versailles

- 5 December–Russia signed an armistice with Germany

- 7 December–American Declaration of War on Austria-Hungary

- 15 December–Armistice concluded between the Central Powers and Russia

1918

- 8 January–President Wilson announced his Fourteen Points program for peace

- 3 March–Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

- 21 March–Germany launched an offensive along the Somme

- 9 April–Germany launched an offensive at Ypres

- 27 May–Germany launched an offensive on the Aisne

- 15 July-7 August–Second Battle of the Marne

- 8 August-11 August–The Battle of Amiens

- 21 August-3 September–Second Battles of the Somme and of Arras

- 26 September–The Allies began their final offensive on the Western Front

- 29 September–Bulgaria signed an armistice

- 3 November–Austria signed an armistice

- 11 November–Germany signed an armistice

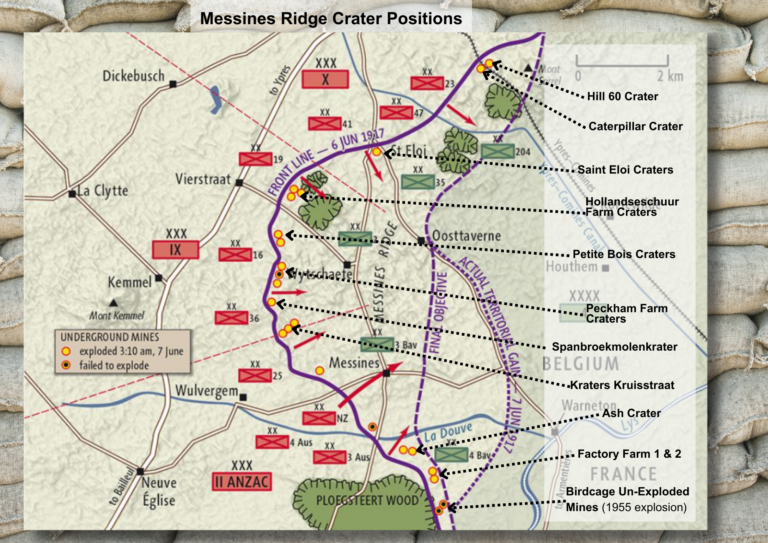

The Spanbroekmolen Mine

The Spanbroekmolen Mine

The mine crater was acquired in 1929 by the Toc H foundation in Poperinge. Sometimes also called “Lone Tree Crater”, it is today recognised as peace memorial[8][9][4] and known as “Pool of Peace”. To its south lies the Lone Tree CWGC Cemetery, to its north-east the Spanbroekmolen British CWGC Cemetery.

The mine at Spanbroekmoelen was started by 171st Tunneling Company, Royal Engineers, on 1st January. Six months later the mine was finished. To celebrate the mine’s completion two officers made their way into the chamber with four bottles of champagne and drinking glasses. The main charge for the mine was made up of 50 LB (pound) boxes of ammonol, totalling 90,000 lbs (pounds). The main charge was finally completed on 28 June 1916 and officially completed, according to the War Diary, on 1 July 1916. (1)

A branch gallery had also been driven in the direction of Rag Point, which was a German position about three quarters of a mile south of the Spanbroekmolen position. In February 1917 the Germans dug a tunnel underneath the British gallery. They set explosive charges to explode two camouflets. As a result the right hand branch of the British gallery was damaged and it was abandoned.

On 3 March 1917 the Germans blew another camouflet which damaged about 900 feet of the main gallery. It broke the connection for the electric detonator leads for the explosive charge which had been lying silently in position under the Spanbroekmolen position since June the previous year.

A new gallery had to be mined to by-pass the damaged tunnel and the detonator leads had to be rerouted through this new tunnel to the chamber and explosives. There was serious difficulty with gas while the new tunnel was being dug. The mine was to be ready to blow at the launch of the major attack on the German lines on the Messines Ridge in June.

In a race against time the new by-pass gallery was completed and tamped. The detonating charge, consisting of 500 lbs (pounds) of ammonal and 500 lbs (pounds) of dynamite was laid on 1 June. The mine was to be fired by power and alternative firing by exploders was arranged in case the electric circuits did not function. The mine was finally completed on the night of 6 June 1917. Major Hudspeth, commander of the 171st Tunnelling Company, sent a message to the headquarters of the 36th (Ulster) Division that night. This division was to attack the German position at Spanbroekmolen at the start of the British attack set for 03.10 hours the following morning, 7 June. Major Hudspeth’s message confirmed that it was “almost certain” that the mine would blow the next morning. The commanders of the 36th (Ulster) Division could only wait in anticipation to see if it did.

The dimensions and details of the Spanbroekmolen mine are as follows:

- depth of charge: 88 feet (26 metres)

- diameter at ground level: 250 feet (76 metres)

- width of the rim: 90 feet (27 metres)

- depth below ground level: 40 feet (12 metres)

- height of rim: 13 feet (4 metres)

- diameter of complete obliteration: 430 feet (131 metres)

- length of gallery: 1,710 feet (521 metres)

The crater has filled with water as a result of the high water table and the clay soil in the area.

The town of Yprés in Belgium is one of the main names which the British associate with the Great War. The area around it was also known as the Salient. This region was fought over from October 1914 until practically the end of the war in November 1918. There were major battles here, including in 1917 the Third Battle of Yprés (often known as Passchendaele after the village).

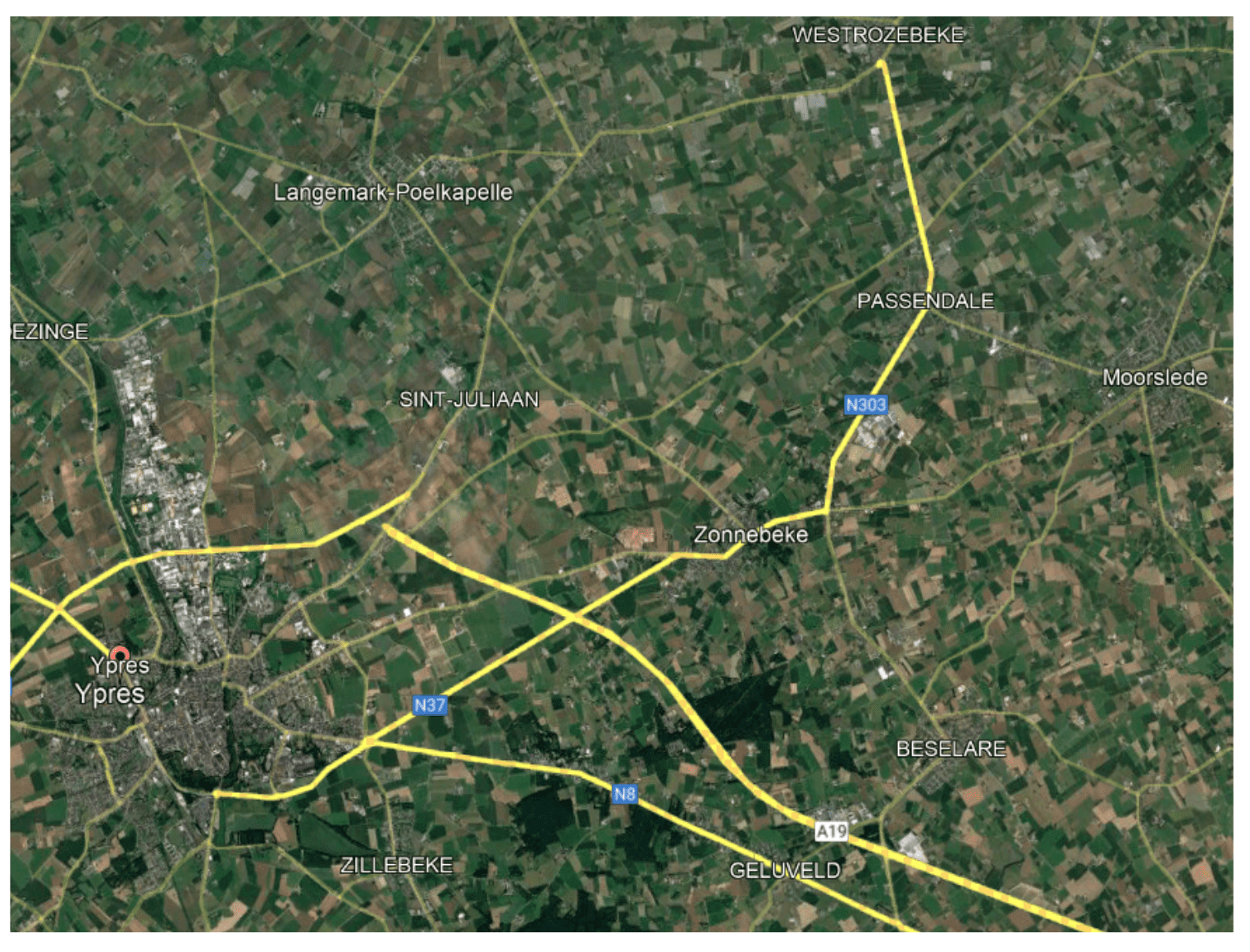

The map below shows the main locations and villages in the Ypres area. The name Flanders was also often used for the region, a medieval state that covered parts of what are now Belgium and Northern France.

Passcehdaele before and after.

Messine Ridge Mines

Several underground explosive charges were fired during the First World War at the start of the Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917). The battle was fought by the British Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer) and the German 4th Army (General Friedrich Sixt von Armin) near Mesen (Messines in French, also used in English and German) in Belgian West Flanders. The mines, secretly planted and maintained by tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers beneath the German front position, killed many German soldiers (approximately 10,000) and created 19 large craters.

The explosions rank among the largest non-nuclear explosions. Before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, told the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”. The Battle of Messines marked the zenith of mine warfare. Just over two months later, on 10 August 1917, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.

Flip Books